Evie Ward writes about how Moki Cherry incorporated parenthood and working with children into a creative practice. Part of a series of editorial exploring motherhood and composing

Mother / Composer by Emily Hall | Imagine! Play! Learn! – by Evie Ward | I choose to celebrate time, by Raf Alero

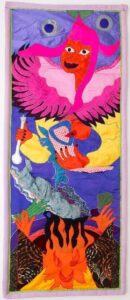

Block-coloured graphic textile appliqué tapestries and paintings, featuring swirling hybrid-species, stylised word-play and psychedelic patterned landscapes. This was Moki Cherry’s first solo exhibition in 1973 at the labyrinthine multi-room Galleri 1 in Stockholm that had vaulted niches and passageways.

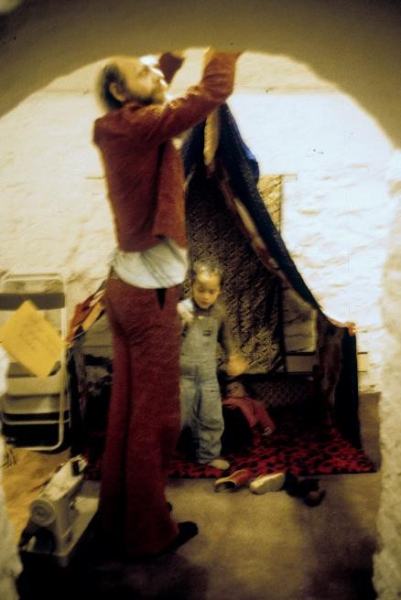

These vaults framed individual compositions of Moki’s works together; in one, stretches of tassels and tiger-striped fabric were draped above a small painting called Energy with a second painting of spiralling words leaning against the wall beneath it. In another vault, an area had been created for children to play and rest: a photo taken in-front of a vaulted passageway shows Moki’s then six-year-old son, Eagle-Eye, with a friend lying down beneath the canopied ceiling of a small fabric den.

Moki’s exhibition and the gallery it took place in was inclusive and multi-functional, it was both where artwork was displayed and experienced, and where she made space for her and other people’s children to rest and play.

L-R: Photo of small fabric den for children through a vaulted passageway, photo of paintings by Moki displayed in a vaulted niche, both at ‘Moki På Galleri 1’, Galleri 1, Stockholm, Sweden, 1973, courtesy of the Cherry Archive, the Estate of Moki Cherry

Children were welcome to roam, explore and engage with Moki’s exhibition, not just as visitors once the show was up, but as part of the install process. A series of photos that follow a small child’s adventures in the gallery simultaneously offer a document of the preparations for the exhibition. In these photos, a child sulks at the camera in front of Moki’s glorious silk and shiny tapestries layered across the gallery floor, kneels next to Aum Expression, a long three metre-wide tapestry of theatrical masks, as it waits to be hung; and holds a colourful, textile appliqué cape made by Moki over their head in front of the tapestry Dha Din Na Dha Tin Na. The playful freedom of the child’s tactile encounters in the gallery while the show was installed gives a glimpse into how Moki approached work with an openness to children actively engaging and sharing space during the different stages of her creative practice. It also demonstrates a certain unfussiness and freedom with her work, where it could be touched and worn as in the case of the child’s cape.

Photo of child kneeling by tapestries by Moki at ‘Moki På Galleri 1’, Galleri 1, Stockholm, Sweden, 1973, courtesy of the Cherry Archive, the Estate of Moki Cherry

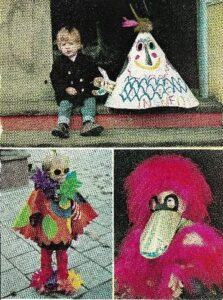

A young mother herself, Moki welcomed children as participants, collaborators and as an audience for her work. Looking back at her career she wrote how “children have always been great supporters, and they have let me understand the work is OK, and [to] never lose hope”.[1] Just one year after having her first child, Neneh, in 1964 and while in the midst of studying at design school, Moki designed imaginative fantastical costumes and small patterned beetle-like papier-mâché creatures for children that were photographed for a magazine. One photo shows a cone the size of a small child decorated with a smiling face and ‘Neneh’ written across its base in child’s handwriting. Arguably Moki’s interest in working with kids stemmed from being a parent herself and in this project with and for children where her daughter’s name is invoked, Moki incorporated her own identity as a mother into her work. Moki’s artworks continued to feature depictions of motherhood throughout her career, such as in an untitled early painting from 1968 where a silhouette of a foetus is embraced by arms made of leaves or in the tapestry Madonna from 1979 of a breast-feeding mother.

Lasse Stener, Photos of children’s costumes by Moki Cherry in a magazine feature, c.1964, courtesy of the Cherry Archive, the Estate of Moki Cherry

At the same time as depicting motherhood in visual work, children were intrinsic to Moki’s wider creative vision that brought together ideas related to the home, including parenthood, with a public experience of her work. This inclusive creative vision encouraged playfulness and the imaginative freedom of children for learning and creativity, where Moki facilitated opportunities for this in and with an artistic environment. For instance back at Moki’s show at Galleri 1, a hand-written sign in Swedish was directed at children inviting them to make drawings for a stand in the show. Moki made space for kids to be creative themselves, so it was not only about children’s presence in the gallery as a consequence of being a parent and representing parenthood in her visual art, but it was also about encouraging, celebrating and bringing visibility to children’s creativity and parenthood in the same context as her art was experienced.

Moki Cherry, Madonna, Textile appliqué tapestry, 1978, courtesy of the Cherry Archive, the Estate of Moki Cherry

The second part of Moki’s hand-written sign asked for a small donation in order to make a children’s corner at Galleri 1. Naima Karlsson, Moki’s granddaughter, archivist and my colleague and friend, told me how Moki brought cooking supplies with her to hotel rooms so that she could make sure there would be food for her children while living on a budget. This sums up the reality of parenting while also being an artist who had to travel for work. Moki wrote, ‘I was never trained to be a female so I survived by taking a creative attitude to daily life and chores’[2] and she subsequently incorporated her role as a mother and caring for her children into a creative practice. The opportunity Moki made for children’s drawings to be shown at her exhibition reflected her pursuits in celebrating children’s creativity and highlighted her own circumstances of being a parent and parenthood generally. At the same time as encouraging children’s artistic explorations in drawings, a children’s corner would have accommodated being a parent by offering child-care and a place for kids to safely play and engage in imaginative creative activities.

Rita Knox, Photo of signs for children’s activities and making a children’s corner at ‘Moki På Galleri 1’, Galleri 1, Stockholm, Sweden, 1973, courtesy Cherry Archive, the Estate of Moki Cherry

Moki’s often quoted motto ‘the stage is home and home is a stage’ described her collaborative interdisciplinary practice with her husband, jazz musician Don Cherry, in their projects Movement Incorporated and Organic Music Theatre. Working together as life partners fundamentally incorporated family-life into their creative output, but it was also something they developed as a practice in facilitating intergenerational and welcoming participatory environments for art and music to be made and experienced in.

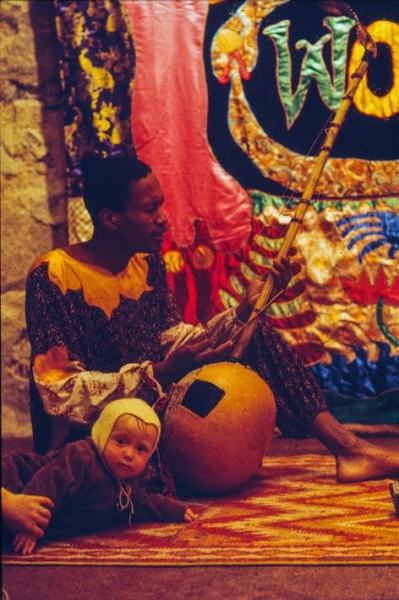

Live music concerts took place at Galleri 1 where Moki, Don and collaborators played in front of Moki’s tapestries. It was common for Moki’s artworks and designs to be experienced in a music-making context as the visuals for her husband’s music. Her work was experienced as advertisements for concerts, album artwork or as aspects of Movement Incorporated and Organic Music Theatre where tapestries adorned the venues where she, Don and their collaborators played music together. The enveloping in multiple fabric artworks by Moki resulted in an inner softer luxuriously textiled environment for music-making, where children were present and also participants, such as in the last part of the video below of Organic Music Theatre in Italy in 1976 where Don and Moki’s children join a performance with them and musicians Nana Vasconcelos and Gian Piero Pramaggiore. In the context of ‘Moki På Galleri 1’, a smaller-scale family-friendly musical environment took place where here again children were welcome and there was certainly no physical line between stage and home in a photo that captures a baby next to Don while he played donso ngoni.

Organic Music Theatre (Don Moki, Neneh and Eagle-Eye Cherry, Nana Vasconzales, Gian Piero Pramaggiore), RAI Studios, Italy, 1976

Don Cherry playing donso ngoni while a baby crawls next to him, in front of Eternal Now tapestry by Moki Cherry, at ‘Moki På Galleri 1’, Galleri 1, Stockholm, Sweden, 1973, courtesy of the Cherry Archive, the Estate of Moki Cherry

The turning point in the Cherrys’ approach in establishing pedagogy as key to their creative collaboration was in 1970 when Don was artist-in-residence at Dartmouth College. This post offered the family financial stability and the Cherrys also collaborated on creating an opera with the students, opening up their home to the student community for rehearsals, and set- and costume-making. This meeting of pedagogy with home and family-life as work planted the seed of how Moki and Don would continue to work and make their home a place for learning and bringing people together. The following year they combined this seedling of an approach with working with children to create an educational children’s TV show our of their home in an old schoolhouse in Tågarp, Sweden. The TV series was called Piff, Paff, Paff, and in it the Cherry kids and other local kids engaged in creative activities and play facilitated by the couple. The activities were in line with Don and Moki’s disciplines and motto, such as making music and textile appliqué costumes, as well as bread-making, and playing in a room surrounded by Moki’s artworks and Don playing piano.

In 1973, Moki and Don put on 88 workshops in schools across Sweden for children. School kids had the opportunity to play music and engage with Moki’s tapestries through touch and as tools for learning music, in tapestries such as Maulkans Raga. In Organic Music Societies, the recent Blank Forms journal about Don and Moki’s collaboration, a quote from Don in Lawrence Kumpf and Magnus Nygren’s essay ‘The Revolution is Inside’ emphasises how much Don valued children’s creativity who ‘are still free to use their imagination, to listen and take part, which I think is important in music. To be able to listen and take part.’[3]

Moki and Don’s endeavours together accommodated parenthood at the same time as developing and making opportunities for work and valuing children’s creativity. However there were some limitations to the Cherrys’ holistic approach to family-life because of having to travel to put on these workshops. For some of the time, the family was separated when Neneh was in school and she was looked after by family and friends.

Photo of Don Cherry standing by Maulkans Raga tapestry by Moki at a children’s music workshop at a school in Sweden, c.1973, courtesy of the Cherry Archive, the Estate of Moki Cherry

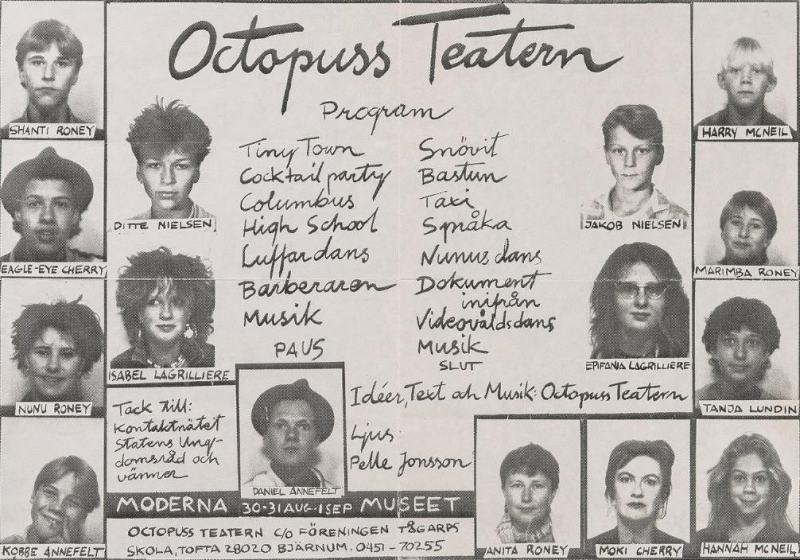

As Eagle-Eye and Neneh grew up, Moki’s methods of working with children and pedagogy grew also. In 1978, she collaborated with her friend Anita Roney, a fellow local parent, on Octopuss Teater, a child-led theatre production company that lasted for eight summers and performed their final productions at Moderna Museet. The two parents coordinated the performances that were based out of the Cherry family home but the productions began with the children, and in fact Octopuss Teater started with the children organising a ‘Children’s Day’ themselves that became a ‘riotously hilarious’[4] cabaret that kids of all ages participated in. A hand-out described their creative process where ‘everybody gets together and starts improvising; its [sic] very playful from the beginning’[4] and how the children ‘have seen, collected and reasoned out everything’[4]. As a result, Moki and Don’s legacy of encouraging creativity and intergenerational learning and participation is embodied in Octopuss Teater, where Moki made the sets and costumes, and the children put their own spin on making inclusive and playful productions.

Program for Octopuss Teater at Moderna Museet, 1985, courtesy of the Cherry Archive, Estate of Moki Cherry

Play and creative learning was a consistent aspect in how Moki worked with children and she facilitated space for it in and with her work. From a child freely playing at Galleri 1 in 1973 to children leading, playing and creating their own theatre productions in Octopuss Teater, the freedom that was encouraged in early pedagogical endeavours developed alongside life’s shifts and the growth of her children and creative pursuits. Moki’s work did not shy away from the realities of being a parent and an artist. Instead she acknowledged and accommodated her circumstances while at the same time making work with children that encouraged creativity and simultaneously nurtured her own creative vision and practice.

Fast forward to today and we notice the resonance of Moki and Don’s joyful and inclusive work in artist-led creative learning initiatives. Spaghetti Club, for instance, is an after school art activity club for kids run by artist Michael Crowe and teacher Emmi Beber. The curatorial duo 650mAh exhibited funny and honest (in a way only kids can be) responses to the art world made by the Spaghetti Club kids at Harlseden High Street gallery in 2020. At the exhibition’s opening, children from the art club did chalk drawings on the floor, there was basketball and hopscotch inside the gallery, intergenerational participatory activities with a desk of worksheets for adults and children that could be pinned to the wall, and a corresponding children’s workshop held at a later date. This exhibition was an opportunity for kids and adults to actively engage in imaginative creative learning and play in the setting of an art gallery. The musician & artist-led Future Music, an experimental music workshop for children ran between 2015-2016 also comes to mind in its emphasis on creative learning methods and improvisation, and it was collaboratively-run by musicians Billy Steiger, Seymour Wright and Ute Kanngiesser, who is also a parent. Workshops took place at Open School East in Margate, Fylkingen in Stockholm, and at Cafe OTO’s project-space in London, where professional musicians (such as the ones who ran the workshop) would also rehearse at. In these, and many other examples, venues that are usually used by adults are opened up to children and their work, echoing Moki’s methods of working of many years earlier, and testament to the creative and nurturing possibilities of hosting inclusive spaces for art making.

References:

[1] Moki Cherry, ‘Work’, c.2004-6, Cherry Archive, the Estate of Moki Cherry

[2] Moki Cherry, note, c.2004-6, Cherry Archive, the Estate of Moki Cherry

[3] Don Cherry quoted in Idestam-Almquist, “Jag vill helst spela för barn,” 6–7, in Lawrence Kumpf and Magnus Nygren, ‘The Revolution is Inside’, Blank Forms 06: Organic Music Societies, eds. Lawrence Kumpf, Magnus Nygren, Naima Karlsson (NewYork: Blank Forms, 2021), 60

[4] Octopuss Teater, ‘This is the Children’s Cabaret!’, paper hand-out, undated, Cherry archive, the Estate of Moki Cherry

Evie Ward is a writer and researcher from London. She wrote a biographical essay about Moki Cherry for the Corbett Vs Dempsey book Moki Cherry: Communicate, How? and is a research associate at the Estate of Moki Cherry.

IG: @_waev_